Table of Contents

Type of Airlines

Not all airlines are created equal. As in most businesses, there is a sort of stratification of airlines. In many countries, the government owns the airlines. An airline’s rank is determined by the amount of revenue it generates. There are three categories in Airlines: Major, National and Regional.

- Major airlines – These are the heavyweights of the airline industry, and you will often hear about them in the news. A major airline is defined as an airline that generates more than £1-billion in revenue annually. Typically, Major airlines are also the largest employers among airlines. However, there are also some major airlines that don’t employ large numbers, which employs only 9,600 people.

- National airlines – Just one step down from the major airlines, these are scheduled airlines with annual operating revenues between £100-million and £1-billion. These airlines might serve certain regions of the country but may also provide long-distance routes and some international destinations. They operate medium- and large-sized jets. Because these are smaller airlines, you can expect them to have a smaller number of employees.

- Regional airlines – As the name suggests, these airlines service particular regions of a country, filling the niche markets that the major and national airlines may overlook. This is the fastest-growing segment of the airline industry and it can be divided into three subgroups:

1. Large Regional

2. Medium Regional

3. Small Regional

Large regionals – These are scheduled carriers with £20-million to £100-million in annual revenue. They operate aircraft that can accommodate more than 60 passengers.

Medium regionals – These airlines operate on a smaller scale, with operating revenues of under £20-million, and often use only small aircraft.

Small regionals – These airlines don’t have a set revenue definition, but are usually referred to as “commuter airlines.” They use small aircraft with less than 61 seats.

The airline industry is just like any other business, meaning that there are numerous types of airlines because their customers have different needs. If you are going overseas, you’re likely to use a major airline because it has more destinations overseas. A business person travelling between two small cities is likely to fly on a regional airline because he or she does not want to have to stop at a major airline hub for a layover.

Airline Business Models

The emerging forms of business models in the airline industry are presented in terms of how the carrier generates revenue, its product offering, value-added services, revenue sources, and target customers.

The deregulation and new competitive interactions between firms always result in some adjustment of the business model to that of the competitor. Three main sets of airline business models that will be described in the next sections are:

1. Full-service carrier or FSC

2. Low-cost carrier or LCC

3. Charter carrier or CC

Full-Service Carriers (FSC)

A full-service carrier (FSC)is defined as an airline company developed from the former state-owned flag carrier, through the market deregulation process, into an airline company with the following elements describing its business model:

- Core business: Passenger, Cargo, Maintenance.

- Hub-and-spoke network: This has as its major objective the full coverage of as many demand categories as possible (in terms of city-pairs) through the optimization of connectivity in the hub.

- Global player: Domestic, international and intercontinental markets are covered with short-, medium- and long-haul flights from the hubs to almost every continent.

- Alliances development: No individual airline has developed a truly global network. Thus the network is virtually enlarged by interlining with partner carriers and become part of multi-HS systems.

- Vertical product differentiation: This is affected by in-flight and ground service, electronic services (Internet check-in) and travel rules to cover all possible market segments.

- Customer relationship management (CRM): Every FSC has a loyalty program to retains the most frequent flyers. The frequent flyers programs (FFP) have become part of a broader strategy called CRM. The general purpose of CRM is to enable carriers to better manage their customers through the introduction of reliable processes and procedures for interacting with those customers. The final aim of the CRM is to enhance the passenger’s buying and travelling experience in order to personalize the carrier services. In this perspective, CRM is an extra tool to differentiate the airline product.

- Yield management and pricing: To support product differentiation, pricing and yield management is sophisticated, with the aim of maximizing network revenues.

- Multi-channel sales: Sales channels are divided into indirect off-line (intermediate travel agencies) or indirect on-line (web intermediate electronic-agents); direct on-line: the passenger buys the tickets directly via the airline’s website; direct off-line: the passenger buys the tickets directly via the airline’s call centre, the airlines city office (CTO), or the airline’s airport office (ATO). The FSC cover all of these channels.

- Distribution system: The complexity of the distribution system described above is technologically supported by external companies called Global Distribution Systems (GDSs). Among the most diffused GDSs are Galileo, Amadeus, Worldspan, Sabre.

Low-Cost Carriers (LCC)

The concept of ‘low-cost carriers’ or LCC originated in the United States with Southwest Airlines at the beginning of the 1970s. In Europe, the Southwest model was copied in 1991, when the Irish company Ryanair, previously a traditional carrier, transformed itself into an LCC and was followed by other LCCs in the United Kingdom (e.g. easyJet in 1995). An LCC is defined as an airline company designed to have a competitive advantage in terms of costs over an FSC. In order to achieve this advantage, an LCC relies on a simplified business model (compared with the FSC), a model which is characterized by some or all of the following key elements:

- Core business: This is passenger air-service despite the ancillary offers are increasing and becoming part of the LCC core business.

- Point-to-point network: The network is developed from one or a few airports, called ‘bases’, from which the carrier starts operating routes to the main destinations. Destinations are only continental within the Europian Union or the United States of America. No connections are provided at the airport bases, which function as aircraft logistics and maintenance bases.

- Secondary airports: City-pairs are connected mainly from the secondary or even tertiary airports—such as London Luton—that are less expensive in terms of landing tax and handling fee and experience less congestion than the larger ones, such as London Heathrow. Small airports will strive to gain the LCC’ operation and the usual way is to reduce airport charges. Similarly, air transport activity generates welfare that is a multiple of the airports’ activities, inducing regional economic and social development. Local authorities recognize that the LCC operation is a potential driver for social and economic developments, and are willing to provide financial help (for example tax exemption, marketing support while LCCs start a new connection). The reduced airport fees can be understood as an incentive, as most of these secondary airports are public. These incentives can be quite relevant and can be deemed to contravene the European Union’s competition rules.

- Single aircraft fleet: In general, the LCC operates with one type of aircraft, such as the Boeing 737 series with a configuration of 149 seats. The fleet composition also depends on the fact that they operate on only short- or medium-haul routes.

- Aircraft utilization: The aircraft is in the air, on average, more hours a day compared with FSCs that have to respect the connectivity schedule.

- No frills service: The product is not differentiated as they do not offer lounge services at airports, choice of seats, and in-flight service, and they do not have a frequent flyer program. Fare restrictions are removed so that the tickets are not refunded able and there is no possibility to rebook with other airlines.

- Minimized sales/reservation costs: All tickets are electronic and the distribution system is implemented via the Internet or telephone sales centre (only direct channels). Passengers receive an e-mail containing their travel details and confirmation number when they purchase. The LCC does not intermediate the sale with travel agents and nor does it outsource the distribution to GDS companies.

- Ancillary services: LCC increasingly have revenue sources other than ticket sales. Typical examples are commissions from hotels and car rental companies, credit card fees, (excess) luggage charges, in-flight food and beverages, advertising space. The potential growth of this revenue comes from telephone operations and gambling on board. Ryanair’s revenue from sources other than ticket sales contributed £259 million to its 2005–06 net profit of £302 million. Those revenues already represent 16 percent of the carrier’s total revenue. For easy Jet, that kind of income originally represented only 6.5 per cent of the airline’s total revenue, but it increased by 41.3% from 2004. Not every low-cost airline implements all of the points mentioned above. For example, in 2005 Air Berlin started the UK domestic services as feeders to its German services out of Stansted, exploring the hub-and-spoke operations. The differences between the FSC and LCC business models are multifaceted. The significant structural cost gap between the two models results from these fundamental differences.

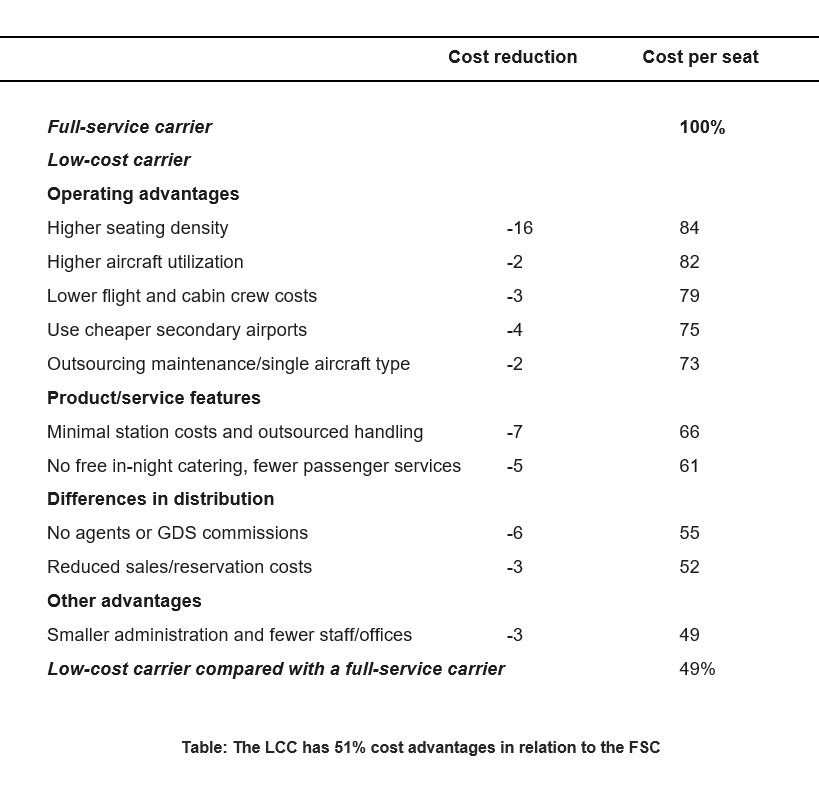

The table breaks down the cost gap between the FSC and the LCC business models. Overall, the LCC model can operate at 49% of FSC costs. In particular, 37% out of a total 51% of costs difference can be attributed to explicit network and airport choices (or business place and process complexity); another 9 per cent of the LCC cost advantage comes from the distribution system and commercial agreements (costs which are narrowing with the elimination of commissions and GDS).

A remarkably small proportion (13%) of the cost differential is product/in-flight service related. The relative simplicity or complexity of their business models distinguishes the LCCs from the FSCs. LCCs have successfully designed a focused, simple operating model around nonstop air travel to and from high-density markets.

On the other hand, the FSC model is cost-penalized by the synchronized hub operations (e.g. long aircraft turns, slack built into schedules to increase connectivity) that implicitly accept the extra time needed for passengers and baggage to make connections. In addition, the FSC business model relies upon highly sophisticated information systems and infrastructure to optimize its hubs. The most relevant success factors of LCCs are their network configuration and their streamlined production processes in relation to FSCs.

- All Courses

- QLS Endorsed – Single Course (681)

- Personal Development (524)

- Career Bundle (375)

- Employability (337)

- Business (174)

- Healthcare (143)

- Management (130)

- IT & Software (122)

- Teaching & Academics (98)

- Health and Fitness (86)

- Design (71)

- Accounting & Finance (63)

- Quality Licence Scheme Endorsed (61)

- Lifestyle (55)

- Hot Deals (52)

- Marketing (42)

- Development (38)

- Health & Care (37)

- Office Productivity (36)

- Technology (16)

- CPD Accredited (14)

- Premium (12)

- Heath and Safety (9)

- Intermediate,Intermediate,IT & Software (3)

Development

Development QLS

QLS Business

Business Healthcare

Healthcare Health & Fitness

Health & Fitness Technology

Technology Teaching

Teaching Lifestyle

Lifestyle Design

Design